Kit Number - 9002

Welcome to Fingerprinting lab! Use the navigation at the top left ☰ to move throughout the lab. Please click on to start the lab!

| Learning Objectives |

|---|

|

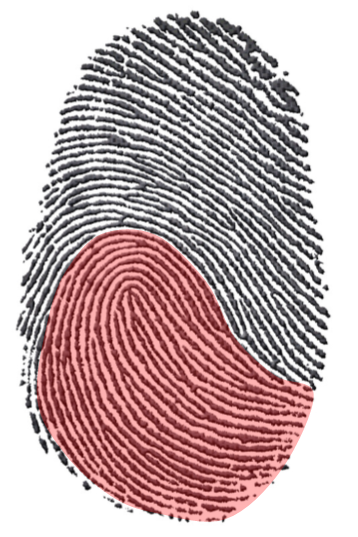

Figure 1: A fingerprint

The patterns of raised skin found on the fingers of every individual are known as fingerprints (Figure 1). Fingerprints develop in the womb, and except for changing in size during growth, the pattern of each fingerprint will remain the same throughout a person's life. They are biometrics, measurable biological features used for identification purposes. Forensic investigators utilize fingerprints to corroborate evidence that a suspect was present at a crime scene. If fingerprints are properly collected and in good condition to be analyzed, they may be admissible in court.

| \(\square\) Is fingerprint evidence always admissible in court? |

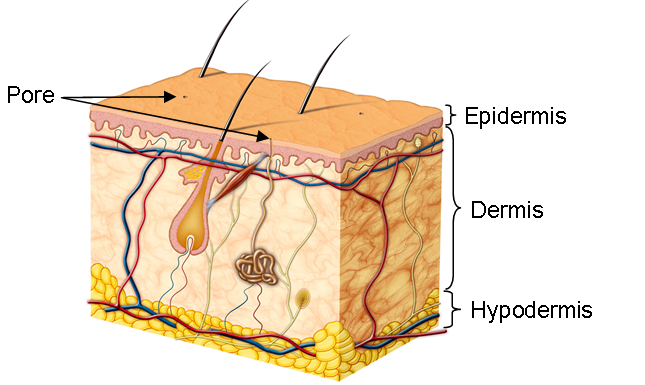

Figure 2: Basic skin anatomy

The skin consists of three layers of tissue: the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis (Figure 2). The epidermis is the outermost layer of skin, and certain areas have a feature called friction ridge skin. The palms of the hands, fingers, soles of the feet, and toes have raised lines called ridges and grooves. Depressed areas between the ridges are called furrows. Friction ridge skin, along with pores (the tiny openings in the skin that secrete sweat and oils), allow the hands and feet to firmly grasp surfaces. Friction ridge skin forms in the 12th to 16th week of fetal development through a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Therefore, a person's genetic make-up is coded to dictate how friction ridge skin will form, but random events, such as fetus's position at a particular moment or the composition and density of surrounding amniotic fluid, influences how every individual's fingerprints form into a distinctive pattern.

Print ridges on finger tips are found in basic patterns with small, distinguishable variations known as minutiae (Table 1). The three basic patterns of finger friction ridge skin include:

| Table 1: Common Ridge Minutiae | |

|---|---|

| Name | Illustration |

| Bifurcation (Fork) |  |

| Double Bifurcation |  |

| Dot |  |

| Delta |  |

| Ridge Ending |  |

| Eye |  |

| Bridge |  |

| Island |  |

| Spur |  |

| Trifurcation |  |

Figure 3: Loop ridge pattern. The area shaded red highlights the looped shape.

Figure 4: Plain whorl ridge pattern.

Figure 5: Plain arch ridge pattern.

Not all fingerprints collected at a crime scene can be used to find a match to a suspect. Partial fingerprints or fingerprints collected from certain surfaces that result in a poor quality print may not reveal enough ridge detail to distinguish minutiae. In addition to the quality of a collected fingerprint, there are other factors that need to be considered when analyzing a fingerprint. While it is accepted that fingerprints are unique to every person, no scientific studies have confirmed the uniqueness of a fingerprint or defined a standard for what constitutes a match. For some prints, eight points may be sufficient. Others may require more to support a conclusion. Examiner skill, experience, subjectivity, and bias may also affect the determination of a fingerprint match. There have been cases in which multiple experienced fingerprint analysts have declared a match between a fingerprint and a suspect who was later proven to be not guilty.

Computer programs, such as the Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS) used by the FBI and state and local authorities, are used to standardize fingerprint analysis and aid in narrowing possible matches from millions of fingerprints in a relatively short amount of time.

Experiment 1: Finger Technique and Minutiae Identification

Experiment 2: Lifting Fingerprintsn